Weekly Economic Commentary

Chief Economist Scott Brown discusses current economic conditions.

The pandemic has changed the economy in a number of ways, but the transformation has been far from settled. Economic growth should continue in 2022, but there are a number of uncertainties, including whether labor force participation will pick up and how aggressive the Federal Reserve will be in fighting the risk of persistently higher inflation.

There were a number of surprises in 2021. Fiscal stimulus was larger than expected, including further direct payments to individuals and extended unemployment benefits. Vaccines arrived sooner than anticipated, although a significant percentage of Americans refused to accept them. Consumer spending and business investment were very strong in the first half of the year. However, the Delta variant and supply shortages, principally the semi-conductor shortage in auto, dampened the pace of improvement in the third quarter. Recent data have indicated a pickup in growth in the third quarter.

The economy is expected to improve further in 2022, but at a more moderate pace than in 2021, largely reflecting reduced support from fiscal policy and the fact that there is less to come back from (the level of GDP is roughly back to its pre-pandemic trend). The Omicron variant is likely to be a near-term constraint on growth, but a temporary one, as we saw with the Delta variant.

Labor force participation is a key uncertainty in the 2022 economic outlook. In November, nonfarm payrolls were still more than four million below the pre-pandemic level and we would likely have added more than three million jobs since early 2020 if not for the pandemic, leaving us more than seven million jobs below the pre-pandemic trend. Labor market constraints have restrained output in a number of industries and are likely to be a limiting factor for overall growth in 2022.

The unemployment rate has fallen sharply (4.2% in November, vs. 6.7% a year earlier), but labor force participation has trended about flat over the last year, well below where it was before the pandemic. Some older workers opted for early retirement in 2020. A small fraction of these have begun to return to the workforce, but early retirements are likely to continue in 2022. Dependent care issues have also been a factor restraining labor force participation. Fewer older Americans have been going into nursing homes during the pandemic. Childcare is more expensive and less available than before the pandemic. Labor force participation should improve. Higher wages could encourage those on the sidelines to return to the workforce, but participation is unlikely to return to its pre-pandemic level anytime soon.

Labor market conditions have continued to tighten. The Fed’s Beige Book (December 1) noted “robust demand for labor but persistent difficulty in hiring and retaining employees.” This has led to widespread wage increases, although most firms are not expected to raise average wages enough to offset higher prices, leading to a continued high level of quits and early retirements. Labor costs have not been the key driver of price inflation, but wage inflation can reinforce higher price inflation – as in the wage-price spiral seen in the 1970s and early 1980s. Yet, the wage bargaining power has shifted significantly over the last few decades. Union membership is a fraction of what it was 40 year ago, while we have seen a much greater concentration of large firms. Firms had increasingly relied on non-wage efforts (signing bonuses, more flexible work schedules or other perks) to attract and retain workers before the pandemic, and these actions should remain at a high level in 2022. Businesses have become more successful in passing higher costs along.

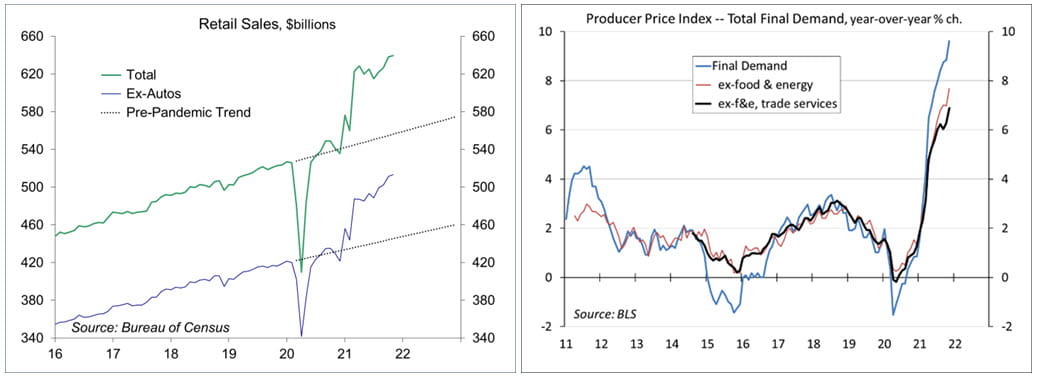

Inflation rose noticeably in the spring of 2021, but increases were narrow across sectors. The rise mostly reflected “base effects” (a rebound in prices that were depressed in the lockdowns a year earlier) and restart pressures. Production bottlenecks and transportation difficulties occur in every economic recovery, but would be more intense this time due to the effects of the pandemic and the rapid strengthening of the economy in the first half of the year. The shift in consumer spending from services to goods has proven long-lasting (retail sales has continued well above the pre-pandemic trend), adding to supply chains difficulties.

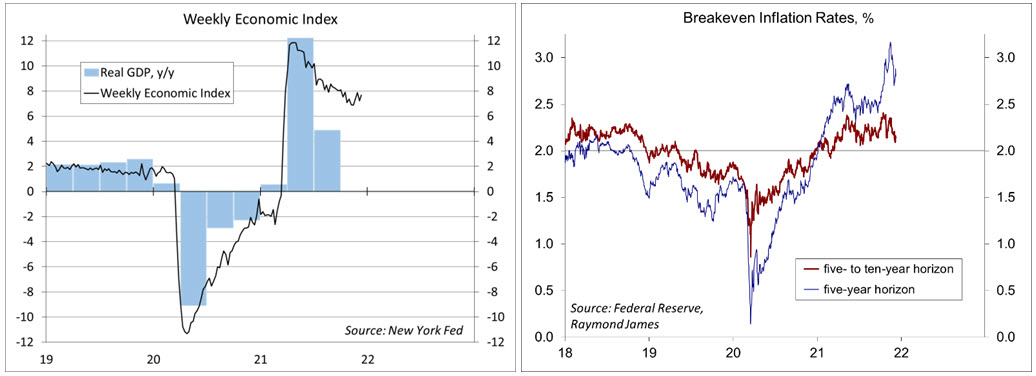

Parts of supply chains have begun to improve, but price increases are now evident over a wider range of sectors, suggesting that higher inflation has become more firmly rooted. The risk of persistently higher inflation has increased. Near-term expectations of inflation have risen, while market-based measures (such as the TIPS spread) imply that inflation is likely to be moderate over the longer term – reflecting the belief that the Fed will act to bring inflation down if it doesn’t come down on its own.

Federal Reserve policymakers began to reduce (“taper”) the monthly pace of asset purchases in November, but will accelerate that reduction in January, and are expected to end purchases completely in March (instead of June). The Fed has stressed that the tapering of asset purchases and the lift-off in short-term interest rates are separate decisions. However, the inflation outlook has shifted dramatically in the last few months. Monetary policy is expected to become less accommodative in 2022, with an initial hike likely to come by the middle of next year (if not sooner). Fed rate increases will depend on how the economy evolves, but the inflation outlook will be the dominant driver.

The risk of a Fed policy error has increased. It’s difficult to engineer soft landings (a smooth transition to a long-term sustainable rate of growth), and there’s a chance that the Fed may either eventually overdo it (raising rates too much and generating weaker growth or a possible recession) or not act soon enough (and have to tighten even more later on in order to push inflation down).

Despite the fear of inflation, long-term interest rates remained moderate in 2021. That is largely because bond yields are much lower outside the U.S. The end of the Fed’s asset purchases might put some upward pressure on bond yields, but most of that should already be factored into the market.

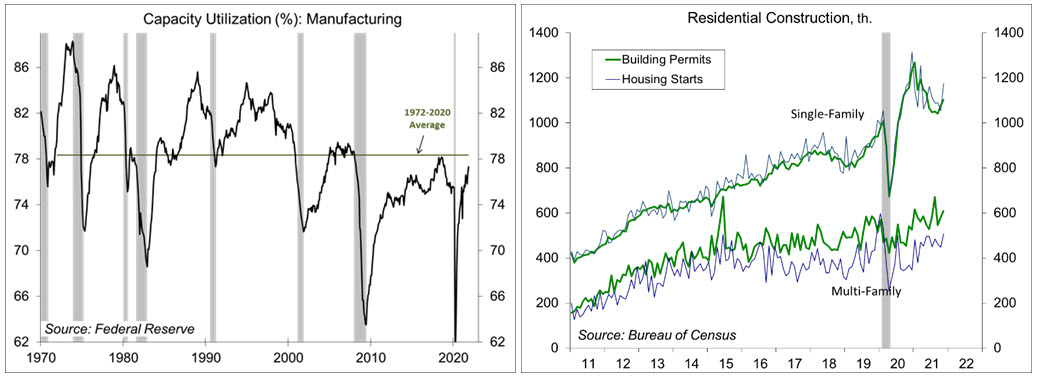

Consumer spending should be supported by further job gains and wage growth in 2022. Commercial real estate is likely to remain generally soft, but robust increases in corporate profits should continue to drive growth in business fixed investment. Affordability continues to be an important issue in residential real estate, but mortgage rates are expected to remain relatively low and demand for housing should remain strong.

The virus and its variants will continue to have an impact on the economy in 2022. While economic activity has moved closer to normal for many Americans, the pandemic has changed work and spending patterns. Working from home has been mostly successful (and more desired) for white collar workers, although blue collar workers still have to show up in person. Consumer spending on services, especially travel and tourism, is likely to recover more slowly.

In summary, the 2022 economic outlook is optimistic, but the view may shift a number of times over the course of the year. Labor force participation, inflation, and Federal Reserve policy remain key uncertainties. Geopolitical tensions, potential cyberattacks, and natural disasters are difficult to predict – and it’s usually the punch you didn’t see coming that does the most damage. Investors should be optimistic as well, but prepare for a shifting landscape.

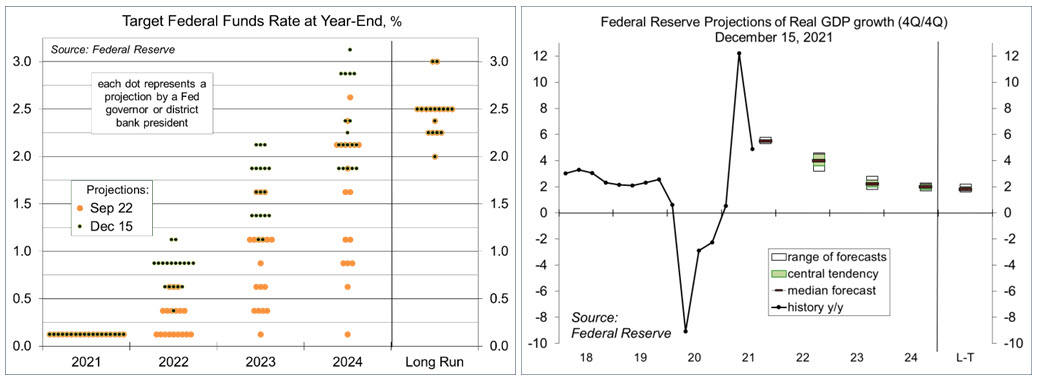

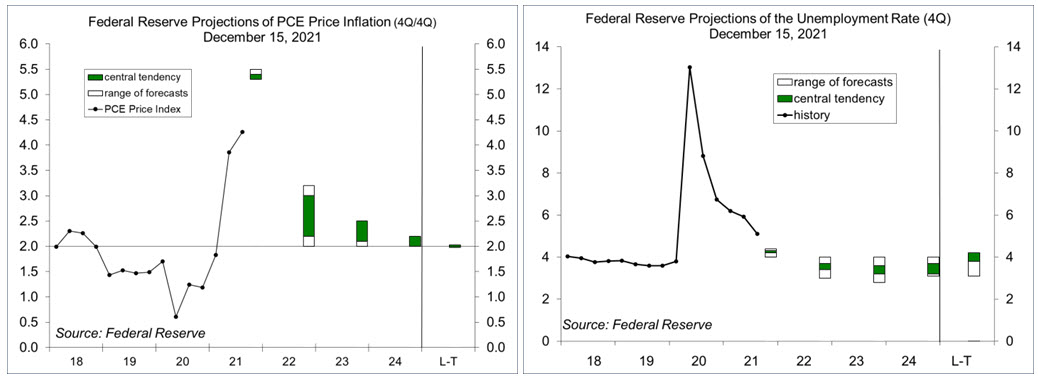

The FOMC Decision and Summary of Economic Projections

As expected, the Federal Open Market Committee accelerated the reduction (“tapering”) of its monthly asset purchases. The policy statement indicated that “job gains have been solid in recent months, and the unemployment rate has declined substantially.” In his press conference, Chair Powell noted that “while the drivers of higher inflation have been predominantly connected to the dislocations caused by the pandemic, price increases have now spread to a broader range of goods and services.”

The revised dot plot (which is a general expectation and not a plan) showed that a majority of senior Fed officials anticipate three or more rate hikes in 2022 (at the September meeting, officials were evenly split on whether there would be even one rate increase in 2022).

The median projection of real GDP growth for this year fell to 5.5% (4Q21/4Q20), down from 5.9% in September and 7.0% in June. While there was a wide range of expectations for 2022 GDP growth (3.2% to 4.6%), the median forecast rose to 4.0% (from 3.8% in September and 3.3% in June).

Fed officials further raised their projections of 2021 inflation (median: 5.3%, vs. 4.2% in September, 3.4% in June, 2.4% in March, and 1.8% last December), but expect inflation to moderate in 2022 (a median forecast of 2.6% in 2022 and 2.3% in 2023).

Fed officials generally expect the unemployment rate to fall further (median forecast for 4Q22: 3.5%).

Recent Economic Data

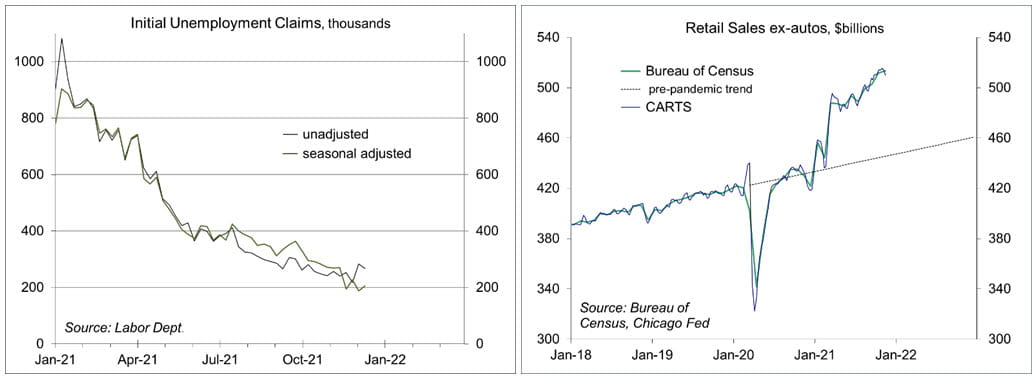

Retail sales rose 0.3% in the advance estimate for November (+18.2% y/y), following a 1.8% jump in October. Ex-autos, retail sales also rose 0.3% (+19.5% y/y). While the monthly increase was disappointing relative to expectations, the level of sales remains about 15% above the pre-pandemic trend.

The Producer Price Index rose 0.8% in November (+9.6% y/y). Ex-food, energy, and trade services, the PPI rose 0.7% (+6.9% y/y). Pipeline inflation pressures remained elevated. Ex-food & energy, the index for processed intermediate goods rose 1.2 (+24.1% y/y), while the index for unprocessed goods rose 4.5% (+32.4% y/y).

Import prices rose 0.7% in November (+11.7% y/y). Excluding food and fuels, import prices rose 0.6% (+5.8% y/y). Most of the increase was in prices of industrial supplies and materials. Inflation in prices of imported finished goods is moderate, but has been trending higher.

Industrial production rose 0.5% in November (+5.3% y/y, but up just 0.3% from two years ago). Manufacturing output rose 0.7% (+4.8% y/y and +2.1% over the last two years), with broad gains across industries led by a 2.2% gain in motor vehicles (down 5.4% y/y and 6.3% lower than two years ago). Capacity utilization, a key gauge of inflation pressure in the past, remains below the long-term average.

Single-family building permits rose 2.7% in November, to a 1.103 million seasonally adjusted annual rate. Housing starts, which are erratic, rose 11.8% (+8.3% y/y).

Gauging the Recovery

Jobless claims rose by 18,000, to 206,000 in the week ending December 11. The figures are volatile in the final weeks of the year. The four-week average fell to 203,750, the lowest since November 1969.

Chicago Fed Advance Retail Trade Summary (CARTS): down 0.8% in the fourth week of November, following a 0.2% drop in the previous week. November retail sales (ex-autos) were projected to rise 0.4% from October (the Bureau of Census reported a gain of 0.3%).

The New York Fed’s Weekly Economic Index rose to 7.69% for the week ending December 11, vs. +7.22% a week earlier (revised from 7.28%). The WEI is scaled to y/y GDP growth (+4.9% y/y in 3Q21).

Breakeven inflation rates (the spread between inflation-adjusted and fixed-rate Treasuries) suggest expectations of higher inflation in the near term, but moderate inflation over the long term.

The University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Index rose to 70.4 in the mid-month assessment for December (vs. 67.4 in November and 71.7 in October), within the narrow range of the last several months. Those in the lower third of income earners reported strong gains, but sentiment for middle-income and upper- income households declined. A quarter of respondents noted “an inflationary erosion in living standards.”

The opinions offered by Dr. Brown are provided as of the date above and subject to change. For more information about this report – to discuss how this outlook may affect your personal situation and/or to learn how this insight may be incorporated into your investment strategy – please contact your financial advisor or use the convenient Office Locator to find our office(s) nearest you today.

This material is being provided for informational purposes only. Any information should not be deemed a recommendation to buy, hold or sell any security. Certain information has been obtained from third-party sources we consider reliable, but we do not guarantee that such information is accurate or complete. This report is not a complete description of the securities, markets, or developments referred to in this material and does not include all available data necessary for making an investment decision. Prior to making an investment decision, please consult with your financial advisor about your individual situation. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss regardless of strategy selected. There is no guarantee that the statements, opinions or forecasts provided herein will prove to be correct.