Imbalanced

Chief Economist Scott Brown discusses current economic conditions.

March CPI data are expected to show more elevated inflation on a year-over-year basis, boosted by a 20% rise in retail gasoline prices (up nearly 50% y/y). Ex-food & energy, inflation will also remain high (about 6.6% y/y), reflecting ongoing imbalances between supply and demand. The Federal Reserve can’t do much about supply constraints, but it can influence demand. Fed Chair Powell is confident that the central bank can engineer a soft landing, returning inflation to its 2% long-term goal, while still maintaining a strong labor market. Financial market participants are more doubtful. This could be a lengthy process, but the Fed is behind the curve and has a lot of ground to make up.

The Fed was convinced early on that a pickup in prices reflected transitory effects, mostly a rebound in prices that were depressed during the lockdowns in the spring of 2020 and the usual supply chain restart pressures which occur after every economic downturn. However, by the early autumn, price increases had broadened out. Near-term inflation expectations have risen, but long-term inflation expectations remain reasonably well anchored near the Fed’s 2% goal. Implicitly, such an outlook assumes that if inflation doesn’t come down on its own, the Fed will make sure that it does. Inflation expectations play a significant role in the Fed’s policy deliberations. However, the current issue is an entrenchment of an inflationary mindset. Supply chain issues and strong demand have driven inflation higher, no doubt, but we’re seeing plenty of evidence that many firms are raising prices simply because they can. That may be a short-term phenomenon, but it’s cause for concern.

Average wages have risen, especially in start-up positions, but have generally not kept pace with inflation. We aren’t in a wage-price spiral yet, but that is a worry. Some firms are more able to pass along higher labor costs. Anecdotally, the flow of job applications has improved. The March ISM Services report noted that labor shortages had “eased slightly” amid declining COVID-19 cases and reduced public health restrictions. However, the job market remains extremely tight. Following annual benchmark revisions and a shift in methodology, the four-week average of claims for unemployment benefits stands at the lowest level since the Labor Department began collecting the data in 1967 (and bear in mind that the size of the workforce is currently more than twice what it was in the late 1960s).

The Russian Invasion of Ukraine has boosted oil prices and disrupted global supply chains. COVID-19 lockdowns in China have led to a backup of container ships off that country’s coast and will likely restrain supplies into the U.S. in the months ahead. Supplier delivery times and order backlogs are rising at a slower pace, but they’re still rising.

Fed Vice Chair Brainard said that “it is of paramount importance to get inflation down.” Currently, “inflation is too high and is subject to upside risks.” Minutes of the March 15-16 FOMC meeting showed that “many” Fed officials wanted to raise the federal funds target by 50 basis points at that meeting, settling for 25 basis points due to uncertainty around the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Looking ahead, “many participants noted that one or more 50 basis point increases in the target range could be appropriate at future meetings, particularly if inflation pressures remained elevated or intensified.” Fed officials worked further on plans to reduce the balance sheet at the March FOMC meeting, reaching a general agreement to set a monthly cap of $95 billion ($60 billion for Treasuries and $35 billion for mortgage-backed securities), ramping up to that level in just three months (in comparison, it took more than a year for the monthly run-off to rise to a maximum of $50 billion during the 2017-2019 balance sheet reduction). The balance sheet totaled $4.1 trillion before the pandemic and now stands at close to $9.0 trillion. The Fed expects a run-off of $1.14 trillion per year. The ultimate size of the balance sheet will depend on maintaining an adequate level of reserves in the system – which is unclear for now.

There is no sign of an impending recession. Of the determinant gauges of recession, nonfarm payrolls, industrial production, and inflation-adjusted business sales are trending higher, while inflation-adjusted personal income (ex-transfer payments) has fallen only slightly. We’re missing all of the pieces for 1Q22 GDP, but net exports and the change in inventories are poised to subtract significantly from the headline growth figure (measures of underlying demand should still be strong). The key predictor of recession, the 10yr-3mo Treasury spread, is still wide, but we could see an inversion later this year. Such an inversion would depend on the FOMC moving the federal funds target rate well above a neutral level (which most Fed officials view as 2.25-2.50%). The balance sheet run-off should act like a rate increase. So, the outlook is complicated and remains highly uncertain. Fed policymakers will be flexible, but inflation must fall.

Recent Economic Data

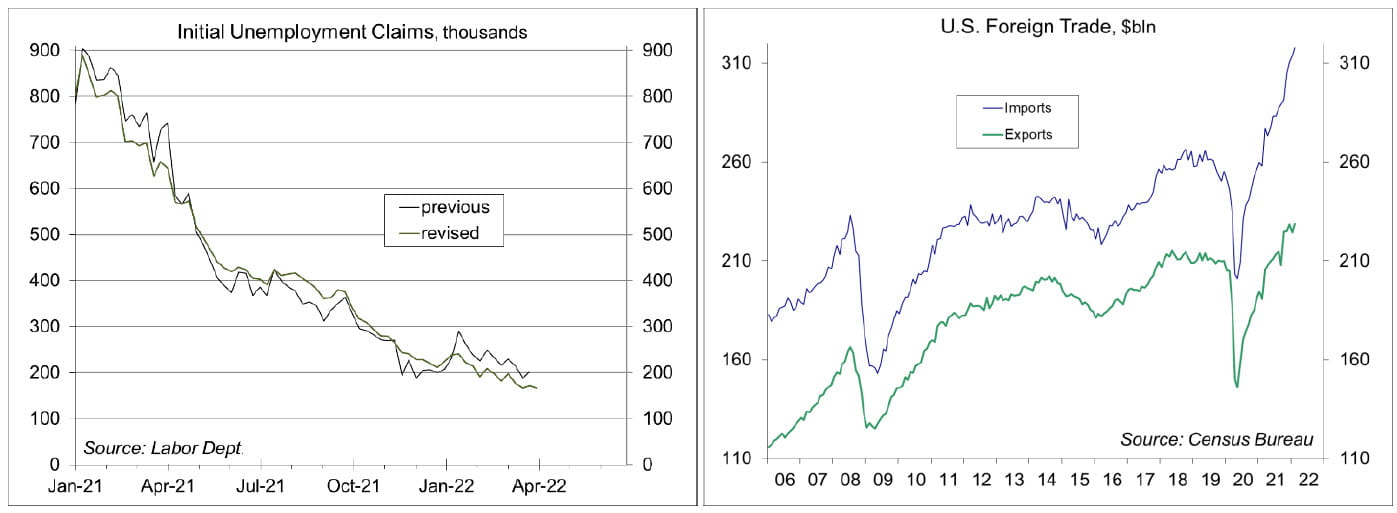

Initial claims for unemployment benefits fell to 166,000 in the week ending April 2. The Labor Department released annual benchmark revisions and returned to a multiplicative seasonal adjustment (it had moved to additive adjustment during the pandemic), which lowered the recent trend. The four-week average was 170,000, the lowest since the Labor Department began collecting the figures in 1967.

The Trade Deficit held steady at $89.2 billion in February, wider than in 4Q21 (a monthly average of $76.3 billion). The February figure was boosted by payments for broadcasting rights to the winter Olympics.

Wholesale inventories rose 2.5% in February (+19.3% y/y), a bit higher than in the advance estimate.

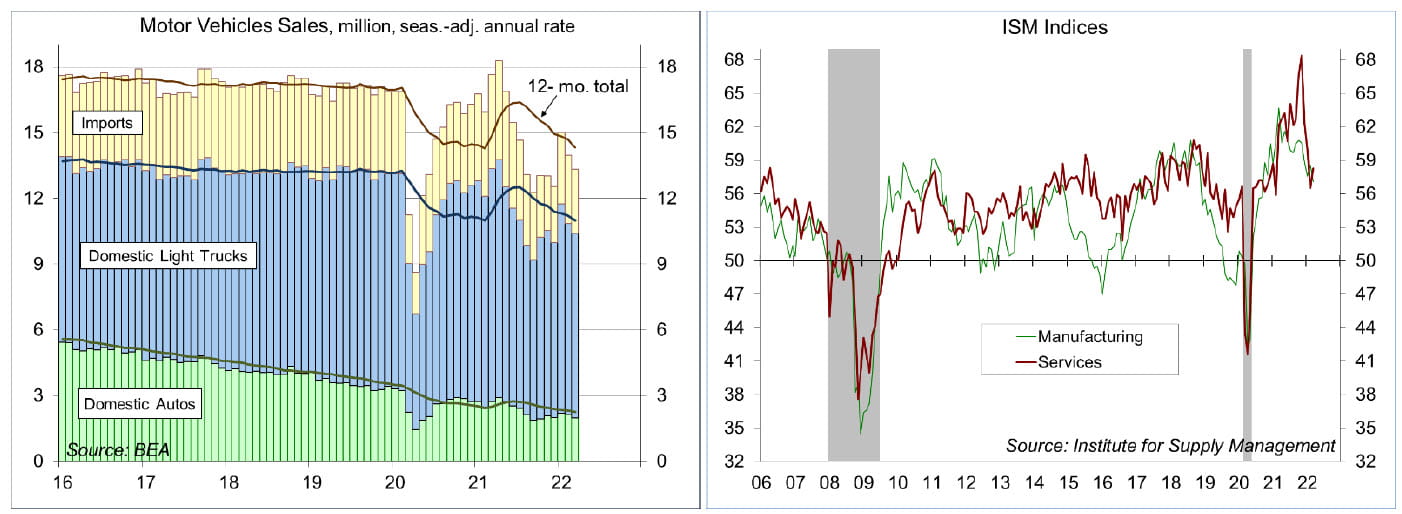

Unit motor vehicle sales fell to a 13.3 million seasonally adjusted annual rate in March, down from 14.0 million in January and 24.4% lower than in March 2021.

The ISM Services Index rose to 58.5 in March, from 56.5 in February, consistent with strong growth (but not as brisk as in late 2021). Supplier delivery times continued to lengthen and order backlogs continued to rise at a rapid pace. Comments from supply managers noted capacity constraints, higher input costs, and labor shortages (which “eased slightly” amid declining COVID-19 cases and reduced public health restrictions).

Factory orders fell 0.5% in February (+12.6% y/y), reflecting a 30.4% decline in civilian aircraft orders. Ex- transportation, orders rose 0.4% (+13.4% y/y).

The opinions offered by Dr. Brown are provided as of the date above and subject to change. For more information about this report – to discuss how this outlook may affect your personal situation and/or to learn how this insight may be incorporated into your investment strategy – please contact your financial advisor or use the convenient Office Locator to find our office(s) nearest you today.

This material is being provided for informational purposes only. Any information should not be deemed a recommendation to buy, hold or sell any security. Certain information has been obtained from third-party sources we consider reliable, but we do not guarantee that such information is accurate or complete. This report is not a complete description of the securities, markets, or developments referred to in this material and does not include all available data necessary for making an investment decision. Prior to making an investment decision, please consult with your financial advisor about your individual situation. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss regardless of strategy selected. There is no guarantee that the statements, opinions or forecasts provided herein will prove to be correct.