U.S. government readies for latest debt ceiling showdown

Senior Investment Strategist Tracey Manzi looks at the factors that are contributing to the current impasse.

To read the full article, see the Investment Strategy Quarterly publication linked below.

Key takeaways:

- The U.S. government has hit its statutory borrowing limit.

- The debt limit is not about new spending, but rather a legislative procedure that allows the government to finance past spending that has now come due.

- Failure to reach agreement on the debt limit has serious, potentially catastrophic consequences for the financial markets.

- We expect that in the end, lawmakers will strike a deal and raise the debt ceiling; however, they will likely wait until the last possible moment.

The debt ceiling is back in the spotlight after the U.S. government hit its statutory borrowing limit earlier this year. While there are steps the government can take to continue paying its obligations, these measures only extend for a limited amount of time. Unless policymakers can agree to raise, suspend, or eliminate the debt limit soon, the government could run out of cash to pay its bills as early as this summer. Failure to reach an agreement would have serious economic consequences, including the risk that the U.S. government defaults on its debt. The stakes are high, and it appears likely that our deeply divided government is headed for another debt-ceiling showdown. Divided governments have typically been good for the markets; however, they often spell trouble when it comes to negotiating fiscal matters.

What is the debt ceiling?

The origins of the debt ceiling can be traced back to 1917 when the U.S. was in the midst of World War I. The new law was initially created to simplify the process of issuing debt to fund war operations. In 1939, Congress established an aggregate debt limit, which has been routinely increased or suspended over the years. Since the 1960s the debt ceiling has been raised 78 times. The purpose of the debt ceiling is to establish a maximum amount of debt the US government can have outstanding. Once the limit has been hit, the federal government cannot increase the amount of outstanding debt until Congress authorizes a new debt limit or suspends it for a period of time. Adjusting the debt ceiling has historically been a routine matter that did not garner much media attention or rattle the markets; however, in recent years it has turned into a political hot button. The most notable confrontation, which pushed the U.S. close to the brink of default, occurred in 2011. Past debt-limit showdowns have typically occurred when there is a Democrat in the White House and Republicans have control of Congress.

What’s behind the current impasse?

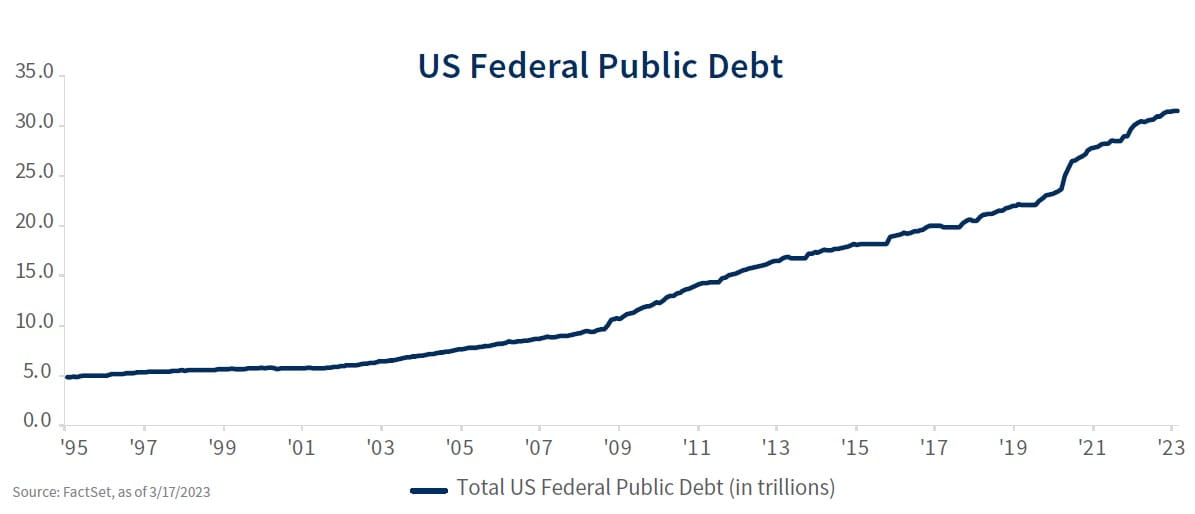

The U.S. government is on an unsustainable fiscal path, with debt and spending growing at an alarming pace. With the huge inflation spike the U.S. experienced last year, fiscal discipline is back on the radar again. House Republicans have made it clear that they intend to push the current administration for budget concessions in exchange for raising the debt limit. Warnings from Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and other high-profile economists about the potential consequences of not raising the debt limit have thus far been ignored. The White House refuses to negotiate as it wants to pass a clean debt limit increase – that is, not tying an increase in the debt limit to the current budgetary process. This is a key point as raising the debt limit is not about new spending, but rather a legislative procedure that allows the government to finance past spending that has now come due. With neither party showing a willingness to negotiate or budge from their positions, it appears likely that we are heading for another showdown in the months ahead. This is important because as we get closer to the ‘x’ date – the date the U.S. government would officially run out of money – the closer the U.S. gets to defaulting. If this were to happen, it would send shockwaves through the financial markets.

Potential consequences for not raising the debt ceiling

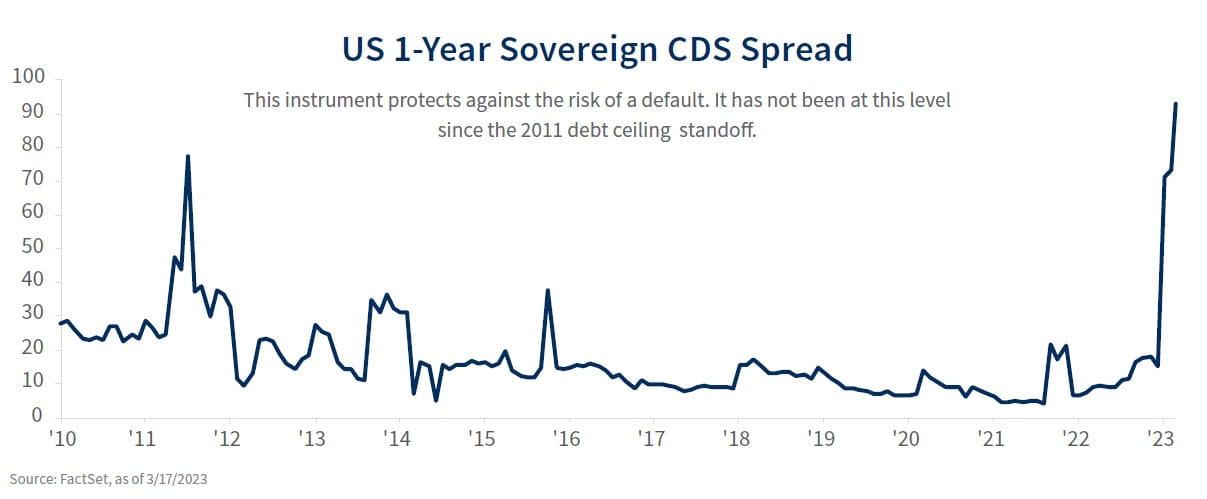

The U.S. government has never defaulted on its debt; however, the market is getting increasingly concerned about the possibility. This is most evident by looking at the U.S. 1-year Sovereign Credit Default Swap Rate (CDS), which protects against the risk of a default. It has spiked to a level last seen in the 2011 debt ceiling standoff. In 2011, the political battle pushed the U.S. the closest it has ever been to defaulting on its debt. The uncertainty created by the political brinkmanship sent the financial markets into a tailspin. With no agreement in place and the calendar getting very close to that ‘x’ date, U.S. equities plunged nearly 15% in just a matter of weeks. The uncertainty spilled over to the international equities markets, which fell nearly 30% while the drama was unfolding in the U.S. The dysfunction in Washington also led to a downgrade in the U.S.’ sovereign debt rating. The market volatility was a key factor that drove the political parties to the table to forge an agreement.

Only time will tell if history is going to repeat itself, but the stakes are high leading into this year’s debt negotiations. The rating agencies have warned that a default would be a catastrophic blow to the U.S. economy, raising borrowing costs across the board and negatively impacting the broader asset classes. And, with U.S. Treasury debt considered the world’s benchmark safe asset, uncertainty about the ‘full faith and credit’ of the U.S. government would have significant spillover into the international markets.

Conclusion

We have been down this road many times before and if history is any guide, lawmakers will eventually strike a deal and raise the debt ceiling. There really isn’t another option, unless there is political will to repeal the debt ceiling law that was established in 1917. Given the deep political divides, it appears we’ll follow a similar track to 2011, where a debt limit agreement is reached, but at the last possible moment. Since we are still months away from the “x” date, the impact on the financial markets has been limited. But, as we draw closer to the “x” date, market turbulence is likely to pick up. However, past experience indicates it will likely be short-lived.

Read the full

Investment Strategy Quarterly

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the Chief Investment Office, and are subject to change. This information should not be construed as a recommendation. The foregoing content is subject to change at any time without notice. Content provided herein is for informational purposes only. There is no guarantee that these statements, opinions or forecasts provided herein will prove to be correct. Past performance may not be indicative of future results. Asset allocation and diversification do not guarantee a profit nor protect against loss. The S&P 500 is an unmanaged index of 500 widely held stocks that is generally considered representative of the U.S. stock market. Keep in mind that individuals cannot invest directly in any index, and index performance does not include transaction costs or other fees, which will affect actual investment performance. Individual investor’s results will vary. Investing in small cap stocks generally involves greater risks, and therefore, may not be appropriate for every investor. International investing involves special risks, including currency fluctuations, differing financial accounting standards, and possible political and economic volatility. Investing in emerging markets can be riskier than investing in well-established foreign markets. Investing in the energy sector involves special risks, including the potential adverse effects of state and federal regulation and may not be suitable for all investors. There is an inverse relationship between interest rate movements and fixed income prices. Generally, when interest rates rise, fixed income prices fall and when interest rates fall, fixed income prices rise. If bonds are sold prior to maturity, the proceeds may be more or less than original cost. A credit rating of a security is not a recommendation to buy, sell or hold securities and may be subject to review, revisions, suspension, reduction or withdrawal at any time by the assigning rating agency. Investing in REITs can be subject to declines in the value of real estate. Economic conditions, property taxes, tax laws and interest rates all present potential risks to real estate investments. The companies engaged in business related to a specific sector are subject to fierce competition and their products and services may be subject to rapid obsolescence.