Fiscal Policy Beyond the Pandemic

Raymond James Chief Economist Dr. Scott Brown discusses the future of fiscal policy and explains why government debt doesn’t mirror personal borrowing.

To read the full article, see the Investment Strategy Quarterly publication linked below.

To counter the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, lawmakers approved $5.2 trillion in fiscal stimulus in 2020 and 2021 – over 25% of annual gross domestic product (GDP) and more than most other countries. At the end of August, the national debt stood at $28.4 trillion. Should investors be worried? What do we mean by “fiscal stimulus,” and have attitudes toward federal deficits and debt changed?

Key takeaways

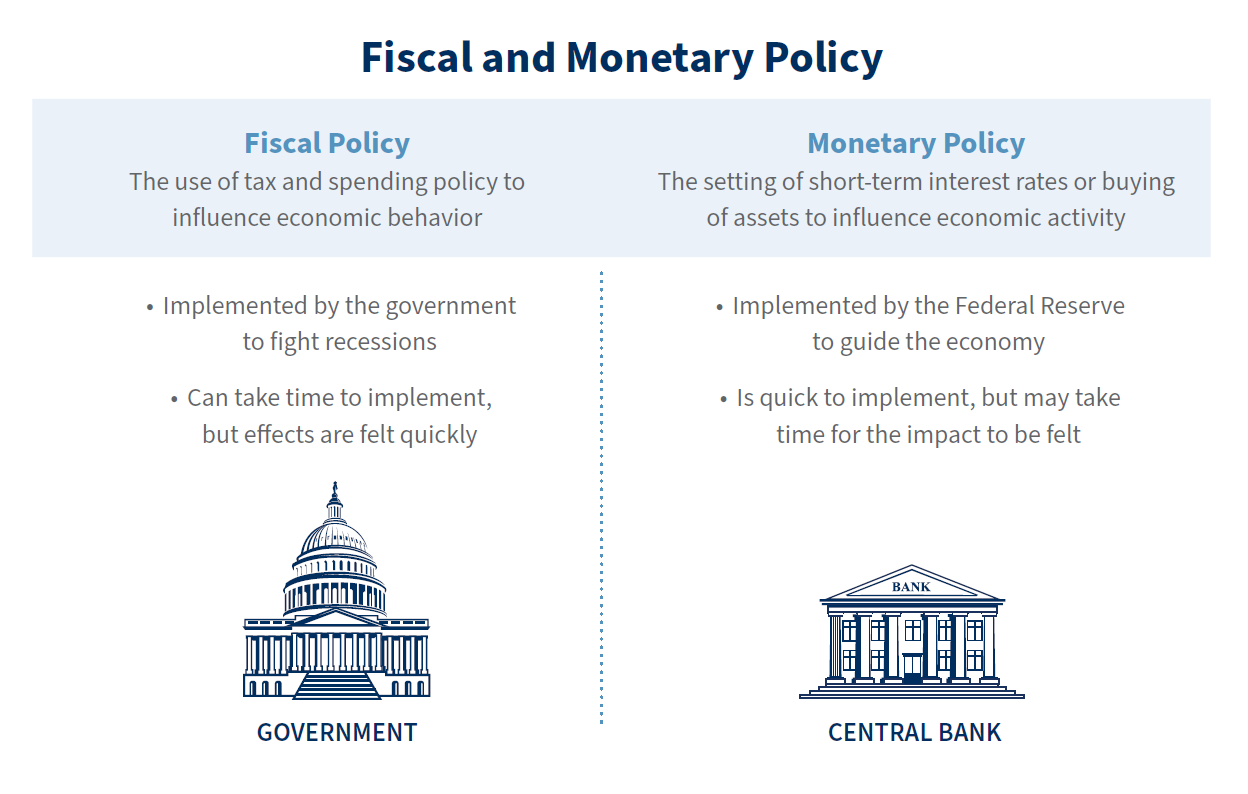

- Both fiscal and monetary policy are used to support the economy. Fiscal policy refers to the use of tax and spending policy to influence economic behavior. Monetary policy is the setting of short-term interest rates (and also, in recent years, large-scale buying of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities) to influence economic activity.

- In a recession, the loss of jobs and income leads to reduced spending, which leads to further job losses, and further reductions in spending, and so on. Fiscal stimulus is intended to halt this snowballing and can be thought of as a bridge supporting aggregate demand while the private sector recovers.

- Should we be worried about the debt? The key issue is whether we can meet interest payments on the debt and whether we can roll over existing debt as it matures.

Where do we go from here?

In July, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the federal budget deficit would fall from 14.9% of GDP in fiscal year 2020 to 13.4% in fiscal year 2021 (ending in September), and then drop to 4.7% of GDP in fiscal year 2022 and 3.1% of GDP in fiscal year 2023. The CBO’s projections are based on current law and do not include the infrastructure bill, which would add a few tenths of a percent of GDP to the deficit in each of the next few years. The important point is the deficit will be coming down significantly, much as it did after the response to the 2008 financial crisis.

The federal budget deficit was on an unsustainable trajectory before the pandemic, around $1 trillion and rising as a percentage of GDP. We don’t have to balance the budget, but we should eventually try to get our fiscal house in order. That means having a deficit that grows no more than GDP, which would stabilize and begin to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio. Achieving this could involve increased tax enforcement and debate about spending reductions, including entitlement reform. Increasing taxes will be difficult, but lawmakers could work to reduce ‘tax expenditures’, the $1 trillion-plus in tax breaks that are embedded in the tax code. The important point is that there’s no need to rush.

Read the full

Investment Strategy Quarterly

Investment Strategy Quarterly is intended to communicate current economic and capital market information along with the informed perspectives of our investment professionals. You may contact your financial advisor to discuss the content of this publication in the context of your own unique circumstances. Published 10/1/2021.