Hope and Fear

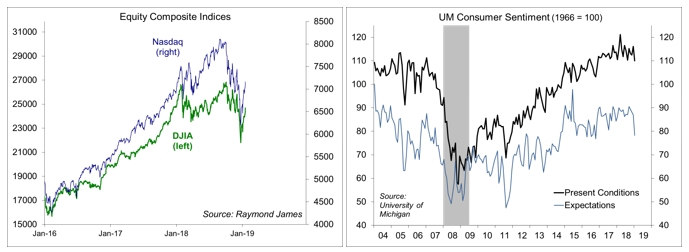

For investors, the year began in fear. The global economic slowdown, the yield curve, Fed policy, trade policy, and the partial government shutdown generated risk. Last week, the news was mixed. There is no sign that the budget stalemate in Washington will end soon. There were renewed reports that President Trump is considering imposing tariffs on all imported motor vehicles. The University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Index fell in the mid-January reading. Yet, there were also reports that the Chinese are willing to make concessions, paving the way for possible progress in upcoming trade talks. The fact that the stock market was willing to ignore the bad news and embrace the good seems to tell us something.

Fear can create fear. In a stock market downturn, investors sell because other investors are selling. The stock market’s march higher into the summer of 2018 was associated with an unusually high level of complacency (and an unusually low level of volatility). However, a list of concerns were growing, and by October became more meaningful. Panic levels remained high in the first few trading sessions of the new year, before Fed Chairman Powell signaled a flexibility on monetary policy and the central bank’s unwinding of its balance sheet. Most economists were nonplussed about what Powell said. Of course, the Fed is flexible. That goes without saying. Powell had already signaled in his post-FOMC press conference that the Fed could be patient in raising rates in 2019. Powell’s comments were self-evident, but they appear to have acted as a slap in the face for the financial markets.

Two of the biggest risks to the economic outlook have been self-inflicted: trade policy and the budget stalemate. The economic impact of both start out relatively modest, but build over time. Both are unnecessary.

Neither side wins in a trade war. Tariffs are a tax paid by U.S. consumers and businesses, not the other country. Tariffs are not necessary to force the other side to the table. There are much better ways. Many had expected the trade conflict with China to end quickly. The trade agreement with South Korea seemed a likely blueprint: make some minor adjustments, declare victory, and move on. This is in effect what happened with the dispute with Canada and Mexico. The U.S. Mexico Canada Agreement is essentially NAFTA with some adjustments in the content requirements in motor vehicles. The disagreement with China has been a different story. For much of the conflict, Chinese negotiators complained that they were unsure of what the U.S. wanted. Indeed, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, and White House National Trade Council Peter Navarro had conflicting approaches (this is reported to be consistent with President Trump’s business strategy of pining subordinates against each other), often in public view. More recently, Lighthizer has emerged as the point person on trade negotiations. That’s a step forward. The threat of an expansion of tariffs on Chinese goods has been disruptive. It’s likely that many firms have stockpiled inventories of raw materials and supplies, although we don’t know because the government shutdown has delayed the release of foreign trade and inventory data. A settlement in the U.S.-China trade dispute would be taken well by investors, and stock market participants appear to be pricing in a favorable outcome.

The government shutdown is having a negative impact on the economy. Federal workers and their families are hurting from missed paychecks. There are secondary effects for businesses that feed into the federal workforce, such as foods services. Unlike federal workers, employees of those firms won’t receive back pay. There is also a disruption to routine services. Airport security lines have lengthened. Mortgage approvals have been delayed. To date, the impact on GDP is likely to have been small, -0.1 to -0.2 percentage point from 1Q19 GDP growth. That impact will increase as the shutdown goes on, perhaps as much as -0.4 percentage point from GDP growth – not enough to push the economy into a recession, but enough to offset the benefits of low gasoline prices and fiscal stimulus. Pressure to settle the stalemate is increasing.

The University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Index fell in the mid-January reading. The report cited ongoing concerns about global growth, Fed policy, the stock market decline, trade policy, and the government shutdown. Bear in mind that the report covers the early part of the month, when investor fear was at its highest. The report noted that the drop in consumer sentiment does not mean that an economic downturn is imminent. Consumer finances (other than federal workers) are in good shape. Job growth and wage gains should continue to provide support for consumer spending.

Fear has subsided to some extent, the Fed will be flexible, and we should see some resolution to trade and budget disputes. That’s good news. However, sentiment can change just as quickly in the other direction, especially if we don’t see progress on trade policy and the government shutdown.

Data Recap – The Bureau of Census reports on retail sales and residential construction were delayed due to the government shutdown. Industrial production rose as expected, but with mixed effects from the weather. The UM Consumer Sentiment Index fell sharply in the first half of January.

The Fed’s Beige Book noted that “economic activity increased in most of the U.S., with eight of twelve Federal Reserve Districts reporting modest to moderate growth.” Most Fed districts reported “modest” job growth, largely because “labor markets were tight and that firms were struggling to find workers at any skill level.” Wages “increased across skill levels, and numerous Districts highlighted rising entry-level wages as firms sought to attract and retain workers and as new minimum wage laws came into effect.” Price increases were “modest to moderate.” Input costs continued to rise, “but reports were mixed on whether they could pass the higher costs on to customers.”

The University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Index fell to 90.7 in the mid-January reading, vs. 98.3 in December. According to the report, “the loss was due to a host of issues including the partial government shutdown, the impact of tariffs, instabilities in financial markets, the global slowdown, and the lack of clarity about monetary policies.” However, the report went on to note that “while the January falloff in optimism is certainly consistent with a slowdown in the pace of growth, it does not yet indicate the start of a sustained downturn in economic activity.”

Industrial Production rose 0.3% in December (+4.0% y/y). Unseasonably moderate temperatures contributed to a 6.3% drop in the output of utilities (less home heating). Mining rose 1.5%, with oil and gas well drilling down 0.3% (+18.3% y/y). Energy extraction rose 1.1% (+16.4% y/y). Manufacturing output rose 1.1% (median forecast: +0.3%), following a weak trend over the three previous months (boosted partly by the effects of mild weather). Production of motor vehicles and parts jumped 4.7% (-8.0% before seasonal adjustment, +7.8% y/y). Ex-autos, factory output rose 0.8% (+0.0% before seasonal adjustment, +2.9% y/y). For 4Q18, manufacturing output rose a lackluster 2.3% annual rate (+2.0% ex-autos)

Jobless Claims edged down to 213,000 in the week ending January 12, leaving the four-week average at 220,750. Note that the regular state totals do not include federal workers, which are normally small. Claims for federal workers are reported with a lag, but we did see an increase into early January (10,454 for the week ending January 5, vs. 4,760 for the week ending December 29 and 1,148 for the same week a year ago).

The Producer Price Index fell 0.2% in December (+2.5% y/y), as a 5.4% drop in energy (-2.7% y/y) offset a 2.6% rise in food (+3.3% y/y). Wholesale gasoline prices fell 13.1% (-14.1% before seasonal adjustment, and -12.2% y/y). These figures do not directly account for tariffs, but the impact of tariffs may be passed along in intermediate goods.

Import Prices fell 1.0% in December (-0.6% y/y), reflecting an 11.6% drop in petroleum (-14.0% y/y). Ex-food & fuels, import prices were flat (+0.6% y/y). Prices of industrial supplies and materials ex-fuels edged down 0.1%, continuing a soft trend after sharp gains in the first half of the year (+2.6%). These figures do not reflect tariffs (which are a tax on U.S. consumers and businesses).

Homebuilder Sentiment edged up to 58 in January, vs. 56 in December and 60 in November, reflecting the retreat in mortgage rates.

The opinions offered by Dr. Brown should be considered a part of your overall decision-making process. For more information about this report – to discuss how this outlook may affect your personal situation and/or to learn how this insight may be incorporated into your investment strategy – please contact your financial advisor or use the convenient Office Locator to find our office(s) nearest you today.

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the Research Department of Raymond James & Associates (RJA) at this date and are subject to change. Information has been obtained from sources considered reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing report is accurate or complete. Other departments of RJA may have information which is not available to the Research Department about companies mentioned in this report. RJA or its affiliates may execute transactions in the securities mentioned in this report which may not be consistent with the report’s conclusions. RJA may perform investment banking or other services for, or solicit investment banking business from, any company mentioned in this report. For institutional clients of the European Economic Area (EEA): This document (and any attachments or exhibits hereto) is intended only for EEA Institutional Clients or others to whom it may lawfully be submitted. There is no assurance that any of the trends mentioned will continue in the future. Past performance is not indicative of future results.