The April Employment Report

Chief Economist Scott Brown discusses current economic conditions.

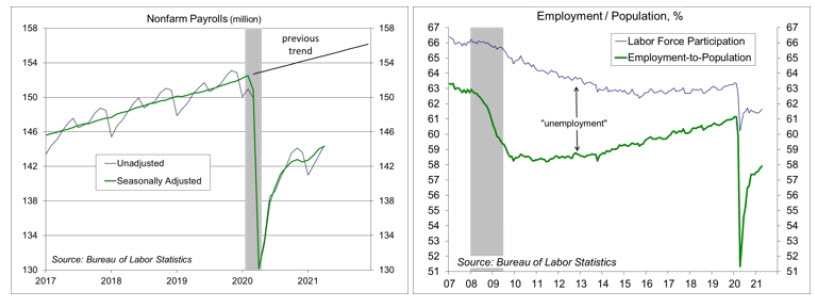

Prior to seasonal adjustment, nonfarm payrolls rose by 1.089 million in the initial estimate for last month, about what we would see in a typical (pre-pandemic) April. The “problem” was that the seasonally adjusted gain was only 266,000 (+218,000 for the private sector). We shouldn’t make too much of one particular month of employment data. The three-month trend remained strong. However, there are going to be labor market challenges as we get back to normal and beyond.

Blaming seasonal adjustment for the forecast miss in the April (seasonally adjusted) payroll gain may seem like a poor excuse, but it is a tricky process. We normally add more than three million jobs between February and June each year. This year, we added 2.27 million in March and April alone. So, don’t worry about the “disappointing” adjusted payroll gain for April. Let’s wait and see what we get in May. More importantly, nonfarm payrolls were down 8.2 million from February 2020 and we would have probably added two million jobs over the last year if not for the pandemic. So, we really have a long way to go.

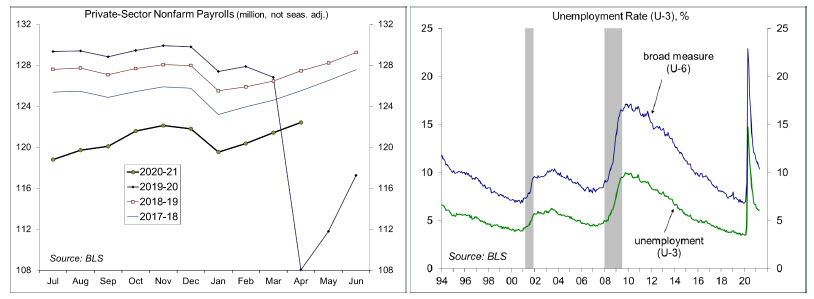

The unemployment rate edged up slightly to 6.1% in April. It would have been lower if not for a pickup in labor force participation. Participation normally rises in a recovery, as those on the sidelines (wanting work, but not officially “unemployed”) become optimistic about finding a job. The employment/population ratio edged up to 57.9% in April, from 57.4% at the end of last year, but still well below the pre-pandemic level (61.1%). While labor for participation is trending higher, it’s going to be difficult to get it back to pre-pandemic levels right away. Childcare issues have contributed to a decline in female labor force participation. Some potential workers fear the virus. Many older workers opted for early retirement over the last year and will be reluctant to return. Generous unemployment benefits and food stamps may also be factors, but for the most part, unemployed workers prefer jobs.

Adding back workers was never going to be as easy as letting them go. It takes time to find workers, to hire them, and to train them. There are huge challenges in matching unemployed workers to available jobs. Potential employees, particularly for lower-level jobs, may not have access to the internet. Others that do have access may not know where to look for jobs. Job fairs and other clearing house solutions are promising, but we’re not seeing enough of that.

Labor challenges are likely to contribute to a bumpy recovery. However, the labor market is likely to go through significant changes over the next few years. Strong demand should lead to a reallocation of labor. Some are expecting the post-pandemic economy to be a “Roaring 20s” environment. Indeed, people will generally be eager to make up for lost time, as they did a century ago (following the 1918 pandemic and World War I). However, the job market may be more similar to the late 1990s. That period had new technologies (including cell phones and the internet), but it was an exceptional period for labor market churn. Millions of jobs are created and lost each quarter. Job losses were extremely high in the late 1990s, but job creation was even higher. The next decade could be a similar transformational period for the labor market, supported by accommodative monetary policy.

Recent Economic Data

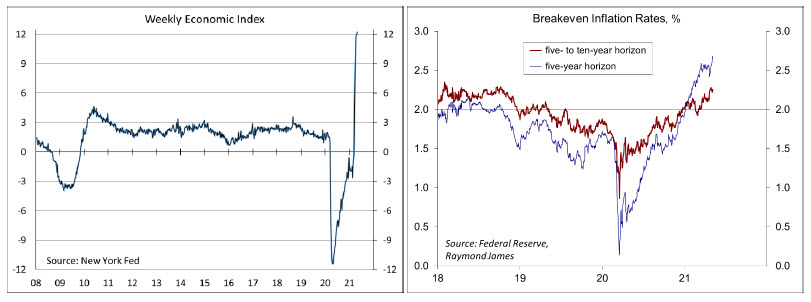

Treasury Secretary Yellen noted that, if enacted, the Biden administration’s proposals would lead to a reallocation of resources and “it may be that interest rates will have to rise somewhat to make sure our economy won’t overheat.” She added that additional spending would be small relative to the size of the economy, but “could lead to some very modest increases in interest rates.”

The ISM Manufacturing Index slipped to 60.7 in April (vs. 64.7 in March), while the Services Index edged down to 62.7 (from 63.7). Both reports noted supply shortages, production constraints and labor challenges, which contributed to inventory reduction and input cost pressures.

Nonfarm payrolls rose by 266,000 in the initial estimate for April, up 1.089 million before seasonal adjustment. Leisure and hospitality continued to rebound, but there was disappointment in manufacturing, construction, and retail. The unemployment rate edged up to 6.1%, reflecting increased labor force participation.

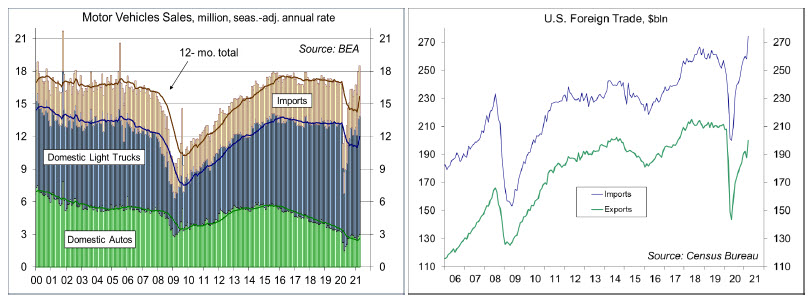

Unit motor vehicle sales rose to an 18.5 million seasonally adjusted annual rate in April (vs. 18.0 million in March and 8.7 million a year ago), the strongest pace since July 2005.

The U.S trade deficit widened to $74.4 billion in March (up from $70.5 billion in February and $47.2 billion a year ago), reflecting strong domestic demand for goods and softer recoveries outside the U.S. Merchandise exports rose 8.9% (+11.9% y/y), while merchandise imports rose 7.0% (+20.8% y/y).

Gauging the Recovery

The New York Fed’s Weekly Economic Index rose to +12.23% for the week ending May 1, up from +12.00% a week earlier (revised from +12.27%), signifying strength relative to the weak data of a year ago. The WEI is scaled to year-over-year GDP growth (GDP fell 9.0% y/y in 2Q20).

Breakeven inflation (the spread between inflation-adjusted and fixed-rate Treasuries) continues to suggest a moderately higher inflation outlook for the next five years. The 5-10-year outlook remains close to the Fed’s long-term goal of 2% (consistent with the Fed’s revised monetary policy framework), but has edged higher.

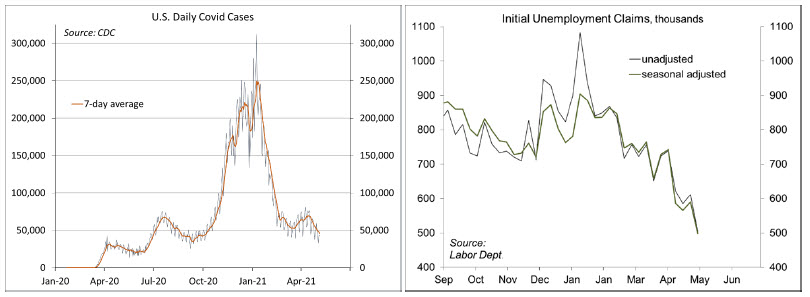

New cases of COVID-19 are trending lower, but the level remains relatively high. Vaccines have helped, but too many people aren’t getting vaccinated, making it unlikely that the U.S. will reach herd immunity.

Jobless claims fell by 92,000, to 498,000 (a pandemic low), in the week ending May 1. Claims are trending lower, but are still much higher than pre-pandemic levels (a little over 200,000).

The University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Index rose to 88.3 in the full-month assessment for April (the survey covered March 24 to April 26), vs. 86.5 at mid-month and 84.9 in March. The increase reflected a growing sense that the upward momentum in jobs and incomes will persist. The report noted a record number of respondents expecting lower unemployment over the next 12 months. According to the report, temporary price hikes are anticipated, but there is some concern that this may lead to a longer-term trend of higher inflation.

The opinions offered by Dr. Brown are provided as of the date above and subject to change. For more information about this report – to discuss how this outlook may affect your personal situation and/or to learn how this insight may be incorporated into your investment strategy – please contact your financial advisor or use the convenient Office Locator to find our office(s) nearest you today.

This material is being provided for informational purposes only. Any information should not be deemed a recommendation to buy, hold or sell any security. Certain information has been obtained from third-party sources we consider reliable, but we do not guarantee that such information is accurate or complete. This report is not a complete description of the securities, markets, or developments referred to in this material and does not include all available data necessary for making an investment decision. Prior to making an investment decision, please consult with your financial advisor about your individual situation. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss regardless of strategy selected. There is no guarantee that the statements, opinions or forecasts provided herein will prove to be correct.