The Fiscal Policy Outlook

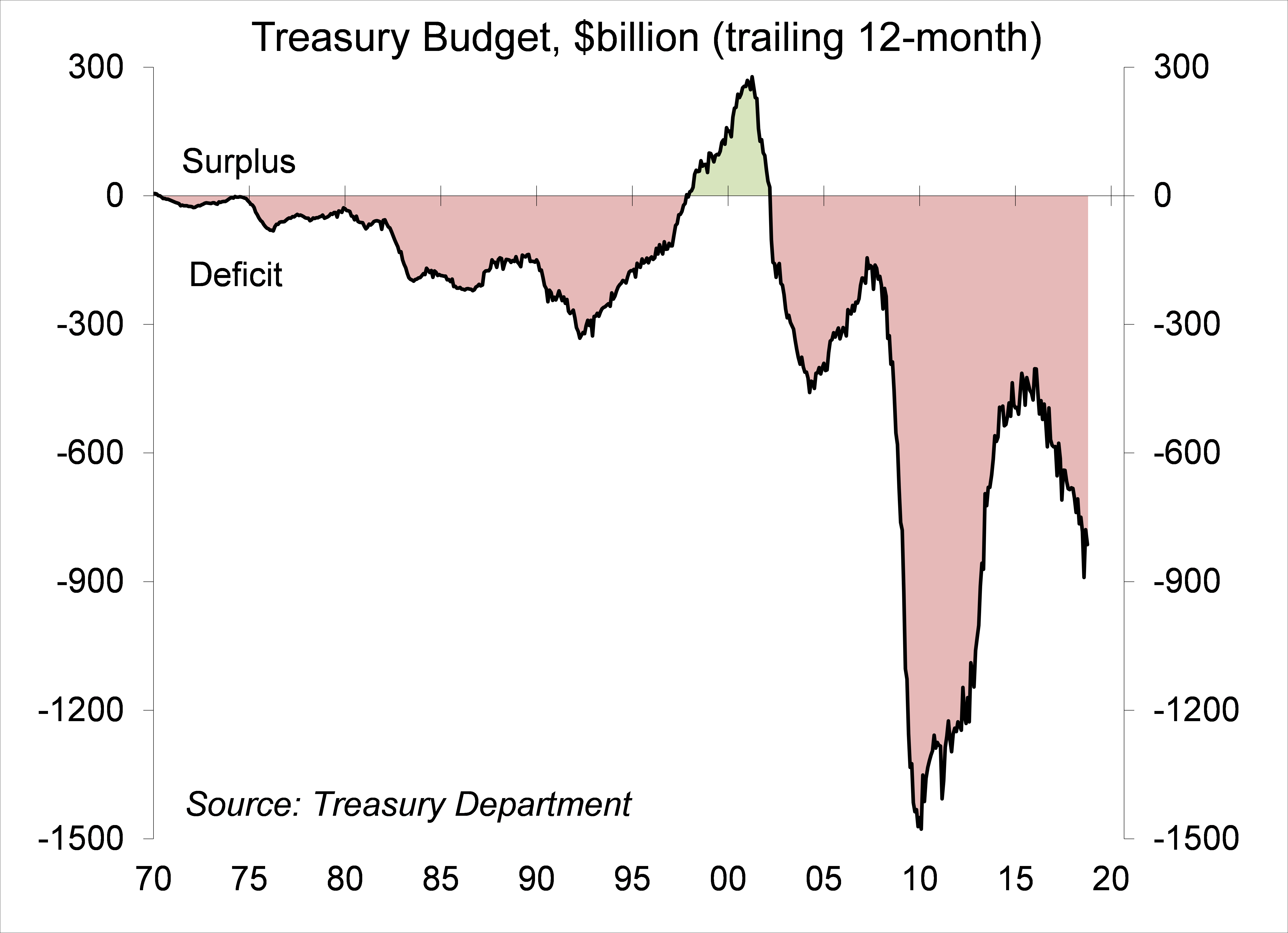

The midterm election results were about as anticipated, with Democrats gaining control of the House and Republicans retaining control of the Senate. Peace, love, and everyone sings Kumbaya, right? The new Congress begins in January. The current Continuing Resolution that funds the government expires on December 7, and we could see a showdown, but it should be easy for lawmakers to kick the can down the road. More troublesome is the deterioration in the federal budget outlook. It’s not a crisis, but budget constraints will limit the scope for further fiscal stimulus, reduce the effectiveness of the automatic stabilizers, and will handcuff lawmakers in their ability to counter a recession.

The federal budget deficit totaled $779 billion in FY18 and is expected to exceed $1 trillion in FY19 – big numbers, but still relatively moderate as a percentage of GDP (about 3.9% and 4.7%, respectively). However, these large and rising deficits come with the economy at full employment. There are no signs of recession on the immediate horizon, but many see an economic downturn as inevitable at some point, and that will increase the deficit further. The switch in House control means we’re unlikely to see “reforms” (that is, cuts) in Social Security and Medicare, which will continue to add to spending totals as the population ages.

There is no cliff effect here. The government currently has no problem borrowing. U.S. federal debt is not going to create a global financial crisis. Debt crises are set up by borrowing in currencies that you don’t control, and the U.S., unlike Greece, has a printing press. The Fed has been raising interest rates which adds to the government’s interest expense, but this has already been factored into budget projections. Still, long-term interest rates should trend gradually higher, reflecting a strong economy, tighter monetary policy, the Fed’s balance sheet unwinding, somewhat higher inflation, and increased government borrowing.

Fiscal policy refers to government spending and taxation. Fiscal stimulus is a reduction in tax rates, increased government spending, or both. Note that there is still some fiscal stimulus in the pipeline for early 2019. The question, following the November 6 election results, is whether we’ll see more stimulus, including a large-scale infrastructure package, in calendar 2019. Most likely, the answer is no. House Democrats are expected to reinstitute pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) rules, which means that any additional spending (beyond what’s already legislated) would have to be offset by higher taxes or cuts to other spending areas.

In a recession, taxes fall and some spending increases (unemployment benefits and food stamps), which helps to offset private-sector weakness. These automatic stabilizers will be less effective in the next downturn (as taxes will have less room to fall).

Many investors worry about foreigners buying U.S. debt – or more precisely, what happens when foreigners stop buying U.S. debt. When we run trade deficits, we effectively borrow from the rest of the world. The dollars spent on imports come back to us, partly into the bond market, helping to keep long-term interest rates lower than they would be otherwise. The U.S. trade deficit is driven by the strength in the domestic economy (we consume more domestic goods and more imported goods), and not by “bad trade deals.” A smaller trade deficit would mean reduced net purchases of U.S. assets. Yet, research shows that tariff increases lead to lower domestic output and productivity, but have only a small impact on the trade deficit. While some of the recent increase in imports may be stockpiling ahead of further tariff increases, we shouldn’t be surprised that tariffs haven’t done much to reduce the trade deficit. In contrast, the larger federal budget deficit means more borrowing from the rest of the world (and implicitly, large trade deficits). None of this should be controversial – it’s basic economic theory backed by plenty of empirical evidence.

The opinions offered by Dr. Brown should be considered a part of your overall decision-making process. For more information about this report – to discuss how this outlook may affect your personal situation and/or to learn how this insight may be incorporated into your investment strategy – please contact your financial advisor or use the convenient Office Locator to find our office(s) nearest you today.

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the Research Department of Raymond James & Associates (RJA) at this date and are subject to change. Information has been obtained from sources considered reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing report is accurate or complete. Other departments of RJA may have information which is not available to the Research Department about companies mentioned in this report. RJA or its affiliates may execute transactions in the securities mentioned in this report which may not be consistent with the report’s conclusions. RJA may perform investment banking or other services for, or solicit investment banking business from, any company mentioned in this report. For institutional clients of the European Economic Area (EEA): This document (and any attachments or exhibits hereto) is intended only for EEA Institutional Clients or others to whom it may lawfully be submitted. There is no assurance that any of the trends mentioned will continue in the future. Past performance is not indicative of future results.